Latinex

News

How many years are necessary to double the cultural and technological advances in our local capital market? And if necessary, how could we measure such progress? Although I don't know the answer, I'm excited to try to find out.

To do this, let's analyze periods of the local market since its foundation in 1989 and compare its evolution at the beginning and end of each interval.

The birth of an idea: From project to reality

1989 – 1999

In 1989, in the midst of a severe political and economic crisis in Panama, a group of visionary businessmen, led by figures such as Frank Kardonski, Ricardo Alberto Arias, Nicolás Ardito Barletta, Guillermo Chapman Jr., and Fernando Aramburú Porras, took the initiative to meet a key need in the financial community: creating a stock exchange. Thus was born the Panama Stock Exchange (BVP), a milestone that established a new trading ecosystem in the country, notable for its security, fairness and transparency.

However, it was on June 26, 1990 when the BVP began to operate effectively. That day the first market transaction was carried out, negotiating Investment Deposit Certificates (CEDIS) from Banco General for a value of USD 940 through a cross order by Capital Traders of Panama. In its first year, although modest in volume, the exchange managed to accumulate USD 3 million through 141 transactions, thus setting an important precedent for the financial future of Panama.

At that time, those who wanted to negotiate their securities had to physically present them in the morning to enable their negotiation in the ring out loud. Later, the negotiation consisted of stockbrokers shouting their offers, a town crier broadcasting them, and a note-taker recording them on a board with red and black markers. Curiously, there was also a space outside the negotiation wheel known as the “negotiation table”, precisely a physical table where agreements were reached on various negotiable instruments such as Tax Credit Certificates (CATS), tax checks, stamps, bills of exchange. change, promissory notes, etc.

Trading pit. 1997.

In the absence of a central custody, operations were cleared and physically settled by BVP itself at the end of the afternoon. For this task, the mechanism used was based on delivery against payment (DVP) of checks signed against physical macro titles. At that time, when the average issuance was around USD 2 – 3 million, this artisanal scheme was operational, but soon the growing market activity would put the scheme to the test.

By the early 1990s, the local capital market was already functional, but faced significant structural challenges. Among them, the tax disadvantage of investing in local securities compared to banking and international instruments. Panama, with a territorial tax system, taxed local source income but not foreign income, which represented a disadvantage for the local financial system. This situation was resolved for the banking sector in the 1970s, but not for publicly traded instruments.

In response, Law 31 of 1991 fiscally equated the local capital market with Panamanian banking and the international market. Thus, the field was leveled so that companies registered with the National Securities Commission and listed on a stock exchange could finance themselves in a more competitive way in the local market.

In 1997, the BVP would promote reforms to the Commercial Code, allowing the creation and operation of a securities exchange. In this way, the Latin American Securities Central (Latinclear) was born in May 1997, segregating and formalizing post-trading tasks and facilitating the immobilization of securities. Despite the technical challenges and the need to “evangelize” investors about the advantages of immobilizing their securities, Latinclear concluded its first year with USD 138 million in assets under custody (Auc).

In 1998, given the exponential growth of its platform, BVP invested significantly in technology to improve efficiency and agility in order execution. With the implementation of the SITREL trading system, operated from an IBM AS 400 the size of a refrigerator, the BVP moved towards electronic trading, leaving behind the colorful outcry ring. Although the term did not exist on that date, that day we became a Fintech.

In 1999, the Panamanian stock market had exceeded USD 1,000 million in negotiations, with the capacity to register 4,780 annual operations and introduce operations and instruments of greater technical complexity. The days of manual trading for USD 940 were behind us.

In addition to these numerical achievements, in 1999, after two years of consultation and drafting, the Panama Securities Law was approved, establishing an adequate regulatory framework that would allow the expansion and development of the Panamanian securities market.

Returning to the initial query of this writing, I wonder if those brokers who executed the first order in 1990, for a conservative amount in a then non-existent market, using pen and paper, clearing and settling trades physically, without a formal regulatory framework and in an uncertain environment after the 1989 crisis, they would have imagined that, ten years later, the market would trade more than USD 3 million daily, its operations would move to the electronic environment and Panama would finally have a stock market environment supported by a law. I do not have this answer, but I sense that in 1999 the stock market would be unrecognizable to any participant transported since 1989.

Entering the new century: Market consolidation and growth

2000 – 2010

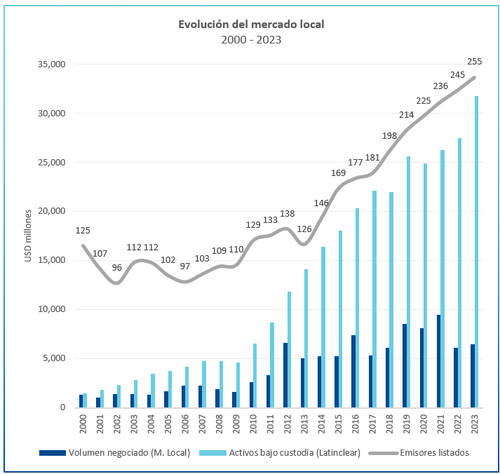

By 2000, Panama's capital market already had 125 issuers, an average daily transaction volume of 5 million dollars and assets under custody of 1,451 million dollars. During that year, a movement was observed towards the consolidation of companies in the real and financial sector through public acquisition offers (OPAs), managed within the capital market. This process led to a temporary decrease in the number of issuers listed on the Stock Exchange, taking with it companies such as Pribanco, Cervecería Nacional, Cervecerías Barú-Panamá and Coca-Cola Compañía Embotelladora de Panamá.

From the regulatory point of view, more than 19 agreements were approved, introducing aspects such as the standards for the presentation of financial statements, presentation of annual and quarterly update reports (INA and INT, respectively), the implementation of exams to obtain licenses and regulations for the promotion of registered broadcasts.

In 2001, Global Bank listed the first issue with a risk rating and in 2002 Hidroeléctrica Fortuna listed the first issue with dual listing in the market; that is, with local and international negotiation. Later, this type of negotiation would give way to important issues registered in Panama that would use the BVP as an international financing channel.

By 2004, the first efforts towards Central American integration began to take shape. This process was evidenced by the crossing of stock market registrations between El Salvador, Costa Rica and Panama. For example, Banco del Istmo and Global Bank were listed in El Salvador, while Banco Cuscatlán and Banagrícola registered their shares in Panama. These actions were a practical manifestation of the ideals of integration promoted by the Inter-American Development Bank, which, since its conference in Washington DC in 1998, advocated the unification of the markets of Central America.

In 2006, BVP was designated as a “designated offshore securities market” by the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) of the United States. In that same year, AES Panama listed the first issue exceeding USD 300 million and the listing of programs for amounts of USD 50 - 100 million was already becoming more common.

Despite the global crisis of 2008-2009, the local market remained resilient, driven by the arrival of new issuers. However, its strength depended largely on the rise and dominance of the banking sector, which represented 34% of the traded volume in that period.

Similarly, banks, through their brokerage houses, exercised significant control over trading platforms. It should be noted that this situation was not unusual in the market structures of that time, where obtaining a position on the stock market required investment in its shares, generating potential conflicts of interest in its direction and governance.

Therefore, in order to overcome the limitations of this model for market development, on October 22, 2009, a process of acquisition and operational reorganization of BVP and Latinclear was undertaken. This process culminated in the consolidation of both operations under the umbrella of Latinex Holdings, Inc. This restructuring allowed the platforms' share base to be opened and led to a series of reforms in corporate governance. These reforms, in turn, significantly reinforced the pillars of security and transparency in the market.

By 2010, after its first 20 years of operation, the local market had made significant progress, experiencing an ADV of USD 11 million, an AuC of USD 8,348 million and represented just over 22% of Panama's Gross Domestic Product. At the end of this period, the capital market had quadrupled in size. In addition, it was formally regulated through the powers granted by the securities law and its trading platforms had been demutualized, evidenced by the public listing of its shares.

In 2010 the local market would be a cause of astonishment for any participant transported since 2000.

Border expansion: From national market to regional hub

2011 – 2021

By early 2011, BVP and Latinclear were already firmly established under the same corporate umbrella of Latinex Holdings, trading under the stock symbol LTXH.

During this period, the Public Debt Market Makers Program was launched, laying the foundations for the negotiation of Panamanian State instruments and evaluating the performance of authorized stock exchange positions through a ranking. In its first year, the program recorded a traded volume of USD 1,278 million made up of 481 operations. Just three years later, this program reached USD 2,022 million.

By 2014, the market exceeded an ADV of USD 22 million and maintained an AuC of USD 16,391 million, representing 33% of Panama's GDP. That same year, Panama positioned itself on the stock market map thanks to the signing of the iLink with Euroclear Bank, a link that allowed the internationalization of Panamanian instruments. Unfortunately, in June 2014, Panama entered the FATF's discriminatory list, thus limiting the scope of the project with Euroclear Bank to Republic of Panama and quasi-governmental instruments, and indefinitely halting the second and third phases of fixed income migration. corporate and variable income, respectively.

Despite the difficulties, Phase 1 of iLink was a resounding success, achieving a migrated balance close to USD 4 billion in its first year and contributing to the construction of a local sovereign curve for Panama in the following years. But the most important thing was the creation of a precedent that allowed international investors to begin to dispel the fear of purchasing instruments with ISIN PAL, establishing direct competition against the traditional issuance format under New York Law. In this context, confidence was gained in the transactions that were successfully negotiated, cleared and settled from the local Panamanian market, thus demonstrating the robustness of its operations.

In 2015, with the aim of realizing the ideal of an integrated regional market, the integration agreement was signed between El Salvador and Panama, opening the way for the unification of the other countries of the Association of Markets of the Americas (AMERCA). In this way, a fraternal bond began between both markets, where the El Salvador stock exchanges obtained direct access to negotiate in Panama and vice versa. This also opened the door to the exchange of business and ideas between investors, issuers, regulators and between the trading platforms themselves.

Image 6. Investors Forum 2015 and 25th anniversary of the Panama Stock Exchange. 2015

In 2017, the first operation was carried out between both markets, reaching a trading volume of USD 17 million in that first year. Four years later, this figure exceeded USD 285 million. Driven by this success, integration processes were initiated with other AMERICA countries, adopting an indirect format through correspondent agreements. Unlike the direct scheme with El Salvador, where recognition between regulators, exchanges and custody centers is necessary, correspondent agreements do not allow direct purchases from the trading screen of the other country, but they do facilitate the clearing and settlement of operations. through the agreements signed between the custody centers. Thus, indirect links were established with Costa Rica (2020), Guatemala (2021), Honduras (2023) and a direct link with Nicaragua (2023).

By 2018, the Panama Stock Exchange had experienced significant growth, processing an annual volume of USD 6.1 billion through 7,635 transactions, which was double the activity recorded in 2011. This notable development made evident the need for a technological and operational strengthening comparable in magnitude to the change in 1998 when the outcry group was replaced. With this objective, the SITREL replacement project was launched, culminating in 2019 with the implementation of Nasdaq ME, a high-end system used in more than 100 markets worldwide.

Panama Day - New York. 2021.

At that time, jokes were made comparing the new platform to the acquisition of a “Rolls-Royce”, due to its operational capacity, much higher than what the transactional volumes of the local market required at that time. However, this investment reflected the long-term vision of the Panama Stock Exchange, which projected itself beyond a national market, aspiring to become a Regional Hub. Therefore, the acquisition of the “Rolls-Royce” was not simply about satisfying an immediate need, but about responding to the future aspirations of the market.

In 2021, despite the economic setback caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Panama's local market reached unprecedented numbers, exceeding USD 9.4 billion in traded volume, with an ADV of USD 37 million, AuC of USD 26.275 million, and a market value of USD 39,941 million, which was equivalent to 53% of Panama's GDP. This milestone was possible thanks to the support of 30 stock exchanges, including 25 local and 5 from El Salvador, as well as 236 issuers from different sectors that maintained more than 1,700 instruments issued and in circulation.

During this period, the average issuance reached USD 50 million, with average annual emissions between USD 100 and 500 million being common. Record figures for the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region stood out, such as the successful placement of USD 1,380 million by AES in 2020, surpassed in 2021 by the USD 1,850 million from Tocumen International Airport.

At the corporate level, Latinex Holdings, whose shares began trading in 2011 with a market capitalization of USD 15 million, already exceeded USD 30 million by the end of 2021.

After 31 years of life, the local market would have facilitated the negotiation of USD 60,435 million in the primary market, providing fresh financing to the more than 500 companies that would participate in the market over the years. These companies, over the same 31 years, generated thousands of jobs and financed hundreds of thousands of homes, as well as energy, commercial, logistics and road projects, contributing significantly to the development of the country. These achievements are a source of pride for all those who have contributed in some way to the growth and evolution of the local market.

In 2021, an important cycle closed with the transformation of the Panama Stock Exchange into the Latin American Stock Exchange, also known as Latinex. This change symbolized the ambition to become a Regional Hub and required overcoming the nationalist sentiment linked to the previous name, recognizing that, to maintain relevance in the coming decades, it was essential to unify resources and expand borders. Thus, the Panamanian stock market was formally opened to the world.

As this third 10-year cycle concludes, I wonder if the participants at the beginning of the decade would have imagined that the market would triple its trading activity, establish a placement link with one of the most important custodians in the world, materialize the concept of markets integrated through different types of link and would cease to be known as a local market and become a Regional Hub.

In 2021, the local market would be a cause of astonishment for any participant transported since 2011, unrecognizable for those who came from the year 2000 and a dream come true for the stock market pioneers of 1989.

Predictions 2050: Always on the move

Present – 2050

Launch of Phase 2 of iLink with Euroclear Bank. 2024.

As I write these lines, the local stock market is consolidated thanks to the achievements made since its founding in 1989. This leads me to reflect on the future of the market in the next 30 years and the achievements that are yet to be achieved. Learning from the last 30 years and avoiding falling into erroneous predictions, I would like to share some goals that, given the trajectory and current context of the market, seem to be achievable:

Panama as a bridge to the international market: After Panama's departure from the FATF list, I predict that we will also soon leave the European Union's black list. This would be for Phase 2 of the iLink with Euroclear, since it would give us access to capital that currently cannot invest in Panama due to regulatory restrictions. Thus, we could offer access to competitive financing, challenging traditional issuance formats under New York Law. Initially, this would benefit medium-sized ISIN PAL issues, expanding the placement capacity of our market and serving as a bridge for international issuers.

Democratization of the capital market: In the past, capital market interactions were carried out in person in a ring out loud. However, with the advent of electronic transactions, this traditional method became obsolete. Although this change brought operational efficiency, it also meant the loss of a significant cultural element of stock trading. Fortunately, in 2022 it was possible to reinvent this space, adapting it for ceremonies such as the “Ring of the Bell” and to promote financial education among young people and professionals. In this way, we have revitalized a key cultural element of the market, which I am sure will be a great contribution to its future development.

At the same time, I see progress in Panama towards regulatory simplification and operational digitalization in the management of investment accounts, bringing us closer to its implementation for the retail public. These advances, combined with efforts in stock market education, will be crucial steps toward market democratization.

The relevance of LAC capital markets will be tested: According to World Bank data, the LAC region represents only 1.9% of global market capitalization. Brazil and Mexico dominate this percentage, with 54.9% and 22.2% respectively, while the remaining 22.9% is distributed among more than 40 markets in the region, adding up to only 0.4% of global capitalization. This contrasts with other regions such as the Middle East and Africa, which represents 5.0%, Europe with 6.2%, Asia with 35.7% and the US with 43.5%.

This disparity is evident both within LAC and on the global stage. At a global level, LAC seems so small that from the outside we are perceived as a single block; However, internally our markets are fragmented by multiple regulatory, cultural and operational divergences.

In addition, LAC markets face competition from large markets such as New York, traditional banking, and private or alternative financing options. In most of these markets, the public sector is the main issuer, limiting the space for local corporate participants. Therefore, competition with more developed platforms, traditional banking and alternative financing channels poses a challenge to the relevance of our markets in the future.

Industry consolidation: Similar to consolidations seen in other regions by entities such as ICE, LSEG, CME, Nasdaq and Deutsche Börse, LAC markets are likely to seek inorganic expansion opportunities. An example of this is the integration of the exchanges of Colombia, Peru and Chile under nuam exchange. Initiatives like these could help consolidate that 1.9% LAC share in a less fragmented market.

Although full unification of LAC markets by 2050 seems utopian, partial consolidations are a real possibility. Our markets tend to maintain the status quo, which makes meaningful change difficult. For this reason, I see the concept of liquidity silos as more feasible, where markets with common regulatory, cultural and operational interests can come together, laying the foundations for future regional mergers and consolidations.

Closing ideas

Ray Bradbury, recognized for his futuristic and dystopian works such as “Fahrenheit 451” and “The Martian Chronicles”, wrote with the purpose of warning us about the actions we should avoid. However, he trusted that the aforementioned reflections will give us clues about the things that we should and can do, will put into perspective the enormous progress that we have achieved in the last 30 years and will serve as a basis of inspiration for the next 30 years, demonstrating that we have lived and will continue to live in times of exponential growth.

Author : Manuel Batista, VP of Finance & Strategic Innovation

Thanks: Myrna Palomo, Edia de Cooban, and Kathia Rivas.

References

Arango, Ricardo Manuel. “Speech Delivered by Ricardo Manuel Arango, President of the Panama Stock Exchange, to the Financial Community Present at the Gala Dinner Offered to Celebrate the 20th Anniversary of the Panama Stock Exchange.” Aug 10 2010.

Brenes, Roberto. “The tax treatment of financial instruments in Panama.” Jan 27 2004.

“Market Capitalization of Listed Domestic Companies (Current US$).” World Bank Open Data, data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LCAP.CD.